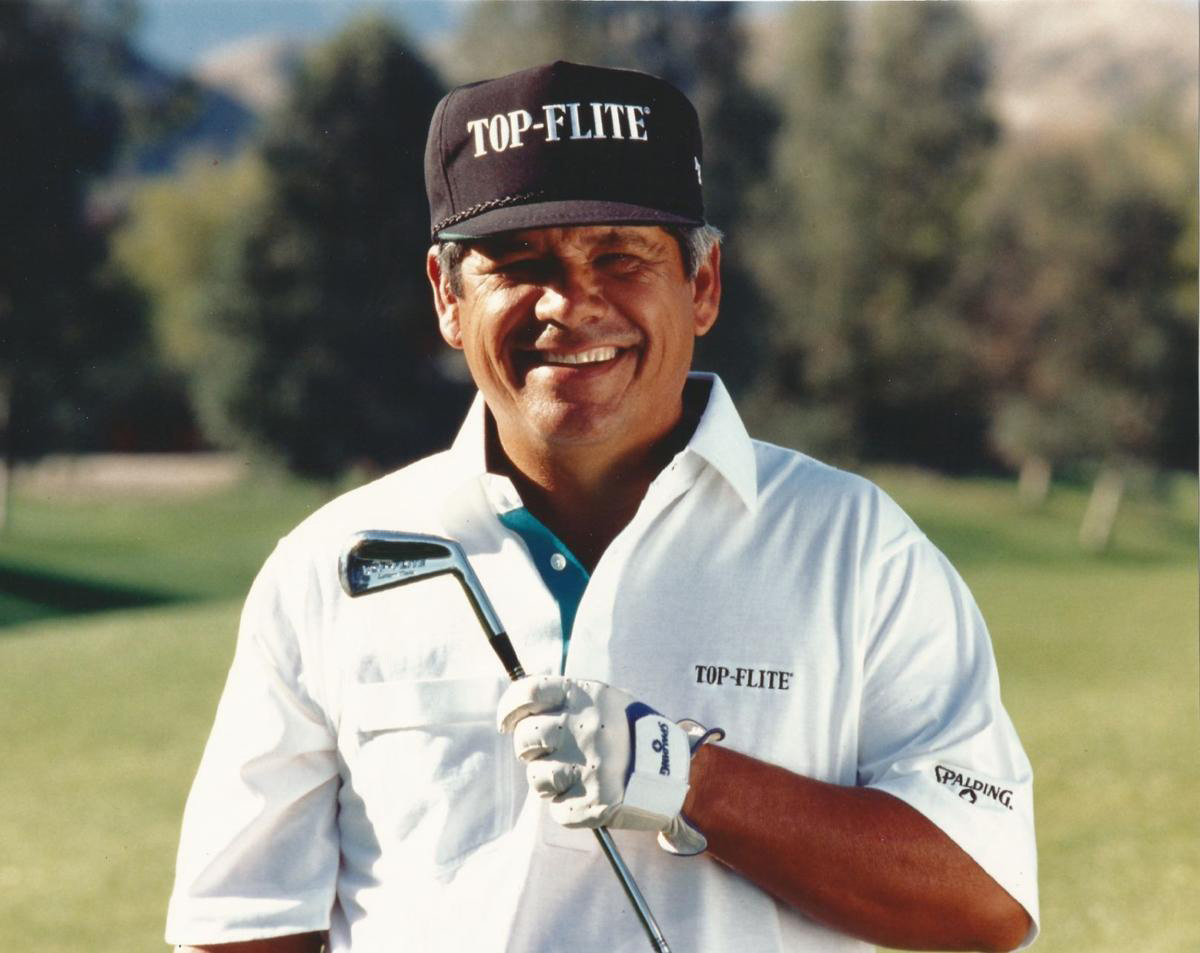

Even at age 80, which he turned earlier this year, Dallas native Lee Trevino still casually towers over the game he lorded over on both sides of the Athletic Ocean.

Even at age 80, which he turned earlier this year, Dallas native Lee Trevino still casually towers over the game he lorded over on both sides of the Athletic Ocean.

With six major golf championships (Two U.S. Opens, Two British Open titles, two PGA Championships), plus dozens of wins worldwide, the World Golf Hall of Fame member cut quite a golfing figure but hasn’t played in an individual stroke play tournament in nine years.

Ask what he did to celebrate his recent milestone birthday, Trevino responded with his usual flair.

“Not much, at home with (wife) Claudia, ate, golf, celebrate. I always ready to go.”

He still plays golf almost every day at a quartet of Dallas courses he belongs to or perhaps elsewhere, always happy to tell stories, polish his reputation as one of the best ball strikers of all times, and take on all comers with a money game or another remembrance of his unlikely career.

Starting with his dirt floor, no plumbing, workers shack where he grew up in this large North Texas city, less than three miles from where he lives today, it would have been impossible to see where his golfing career could have taken him.

“When I showed up, people said where the hell did he come from and when I leave, people will say where the hell did he go? That’s just the way I want it,” with that, he lets out his trademark hearty laugher which earned him the nickname, the Merry Mex.

Just consider the Trevino plotline. A young, poor Mexican golfer never knows his father, raised by a mother and a grave-digging grandfather, with no money, no golf clubs, and no golf lessons.

He’s introduced to the game by his caddy master uncle, Lupe, who never played the game himself, but shows Trevino how to caddy for rich members and building golf courses. Then Trevino steals away with little time he has left, teaching himself a game he had learned from watching club members’ swing.

From the dusty shack, long since paved over for Central Expressway in Dallas to his current multi-million dollar lifestyle, completed with luxury automobiles and expensive tailored clothing, Trevino’s life, and career are finally in full view.

Possibly no one in golf achieved more with less in the game of professional golf than one Lee Buck Trevino.

“I never thought about this growing up, I couldn’t,” he said. “I was only thinking about a better house, a nicer car, and drinking more beer. Now I’ve got the house, have a really nice car, but don’t drink anymore.”

To say Trevino’s upbringing and the ultimate outcome is the stuff of legends is to overlook how legendary it was.

He didn’t overcome his life circumstances, he transcended them.

Even his non-stop, on-course banter is entirely homemade. Growing up as a caddy at Glen Lakes Country Club (the original Dallas Athletic Club location), caddies weren’t allowed to play, so Trevino and his friends carved out their own three-hole course in the woods next to the course. They could only scrape together one set of clubs which had to be shared among all players.

“We’d be walking down the fairway saying, ‘how Pedro, I need the 5-iron. Hey Whitey, I need the putter,’ and that’s how I started talking all the time on the golf course.”

After growing up caddying at Glen Lakes and playing golf at public Tenison Park Golf Course with a taped-up Dr. Pepper bottle, which his sons still have, he got his first taste of real competitive golf during a stint in the Marine Corps ending in 1965.

A brief falling out with his mentor Hardy Greenwood, who ran Hardy’s Par 3 in Dallas, led to him to El Paso, as an assistant pro at Horizon Hills Golf Club, where he continued his gambling and hustling ways.

Future World Golf Hall of Fame member Raymond Floyd, already a PGA Tour winner, came to El Paso in ‘66 looking to make an easy mark from the money-heavy West Texas crowd.

Floyd and his financial backers rolled up to the clubhouse and out bounced Trevino to grab Floyd’s clubs, point him to his room and begin shinning his golf shoes.

While his handlers went out to get a cart so Floyd could scout the course, the young North Carolina golfing hotshot asked his new helper who was the local star player he would be facing in the three-day match.

“That would be me, Mr. Floyd,” Trevino said looking up from his cleaning duties.

“I’m playing the shoeshine guy, I don’t need to scout any course,” Floyd told his backers

But Trevino won the first day, shocking Floyd who immediately asked for an emergency nine to reclaim his money.

“I’m sorry, I can’t Mr. Floyd. I have to put in all the carts before dark,” Trevino truthfully said.

The result was the same on day two before Floyd finally won his money and some pride back on the third day when Trevino narrowly missed an eagle putt on the 18th hole.

Ask years later to confirm the details of that Texas money match, Floyd could only shake his head.

“Lee wrote about it in his book, I wrote about it in mine. It’s all there and all true,” Floyd said.

Trevino realized his education in the school of hard knocks was finally complete and the next hurdle would be the PGA Tour. He turned pro in 1967 and shocked the golf establishment by finished 5th in the U.S. Open at Baltusrol and named Rookie of the Year.

For every step along golf’s professional competition ladder, Trevino tightly guarded the two things which no one could add or take away, his passion and his unshakeable belief in his own abilities.

“Life is all about passion, you have a passion for your job, for your marriage, for your life. I had that passion and nobody could take it away,” he said.

He returned to the U.S. Open in 1968, winning his first golf major by four shots over Jack Nicklaus, for his first-ever PGA Tour win, and became the first golfer ever to shot all four rounds in the 60s in a U.S. Open.

Afterward, it was Trevino paid tribute to his Texas heritage as the first Mexican-American golfer ever to win a major championship, “my own goal is to make enough money to be able to buy The Alamo and give it back to the Mexicans.”

Perhaps not surprisingly with home homemade swing, Trevino achieved as much success at the British Open as any of the other major championships, recording six Top 5 finishes at the Open, including a tie for third at The Old Course in 1970.

“My strong suit was the driver. I could put it on the sidewalk and I knew I could. I never feared anything. It didn’t matter to me if it had a fairway I will hit that. If it has a green I will hit that. It doesn’t matter if it had animals and snakes. I would be in the fairway.

To prepare for his Open title defense in 1972, Trevino took a Lone Star route of preparation. He asked his Texas golf and military friend Orville Moody to find him a place where he could train in peace and privacy.

Moody knew of a Central Texas course that had not opened yet on a nearby Army-based and arranged for Trevino to make it his Murfield Open training camp.

“I played 18 holes every morning, running after every shot. Then I would come home and have breakfast, then hit balls for a couple of hours. I’d have lunch, swimming with the kids and then at 4 p.m. play some more. I did that for a week to go defend at Murfield. I was practicing bump and run and all the shots I would need.”

Trevino’s loud, outgoing personally bothered several players including Britain’s Tony Jacklin on many occasions and led to another famous, but true Trevino quote, when they played in the semifinals of the World Match Play at Wentworth in the early 1970s.

Walking to the first tee, knowing what to expect from his opponent, Jacklin turned to Trevino and told him they were going to have a serious match with no talking.

“Tony, you don’t have to talk today, just listen,” Trevino said with another huge laugh.

The pair combined for 26 birdies and three eagles in the 36-hole match which turned out to be another Trevino victory.

Other than the pair of Open victories, Trevino said his greatest major thrill was beating Nicklaus in an 18- hole playoff to claim his second U.S. Open title at famed Merion Golf Club

“Anybody can win a sudden-death playoff, but to win in 18 holes, when I beat the best there is, it gave me the confidence and I felt like now I belonged. I can play with the best.”

It was the match where Trevino threw a rubber snake at Nicklaus on the first tee, a move Trevino said Nicklaus knew was coming and actually ask to see.

While his major thrills were glorious, Trevino has a searing memory of his one great golf regret, his inability to win a Masters title at Augusta National Golf Club.

He said it was an early run-in Masters ruler Clifford Roberts, a clash of personality styles, which caused Trevino to miss out on winning all of golf’s majors.

“It wasn’t the golf course as I’ve always led on to be, it was Cliff Roberts. No question I would take a different way today. I would have kept my mouth shut and respected the fact that Mr. Cliff Roberts was the one who ran the place, but I felt like he should respect me and see where I was coming from.”

Trevino was burned literally in 1975 when struck by lightning on course during the Western Open in Chicago, a condition which bothers for years and led him to Germany for a back operation that finally cured his pain.

“When I was hit by lightning 1975, I had nowhere else to go, I didn’t have any other options, I had to come back. If I had a master’s degree in something else, I would have quit. You didn’t think about quitting when you don’t have any other options.

These days he’s more than content to spend most of his days at his Dallas home with his third wife, Claudia, who he calls his rock. His considerable golf winning, including an all-time record 29 times on the Champions Tour, are protected by a professional investment firm and audited twice a year to make sure there is no unexpected loss.

He has a place in Palm Springs he goes to in the wintertime and once lived in Florida before returning home to Texas saying, “I wanted to make sure I didn’t die in some damn Florida condo.”

“I tell people I don’t do anything all day long and don’t get started with that until noon,” he said with another trademark laugh.

There is always more casual golf to play, more fun trips to take, more stories to tell.

The one Trevino would like people to tell about him is simple.

“I made it as a poor man in a rich man’s game. I broke the mold because nobody had ever won like this with my background. I made it in a rich man’s game, that’s what I’d like for them to say.”

By Art Stricklin